A fundamental theory of quantum gravity remains one of the most significant unresolved issues in physics. To illustrate the enigmatic nature of gravity at the quantum level, consider a simple thought experiment in electromagnetism. Imagine a superposition of a positive and a negative charge that you are trying to keep coherent over a long period. This task is extremely challenging because the surrounding environment causes decoherence. The degrees of freedom in the environment interact differently with each component of the superposition, leading to a loss of coherence. Let us provide you with all the necessary tools to eliminate the environment. How long can you hold the superposition in place?

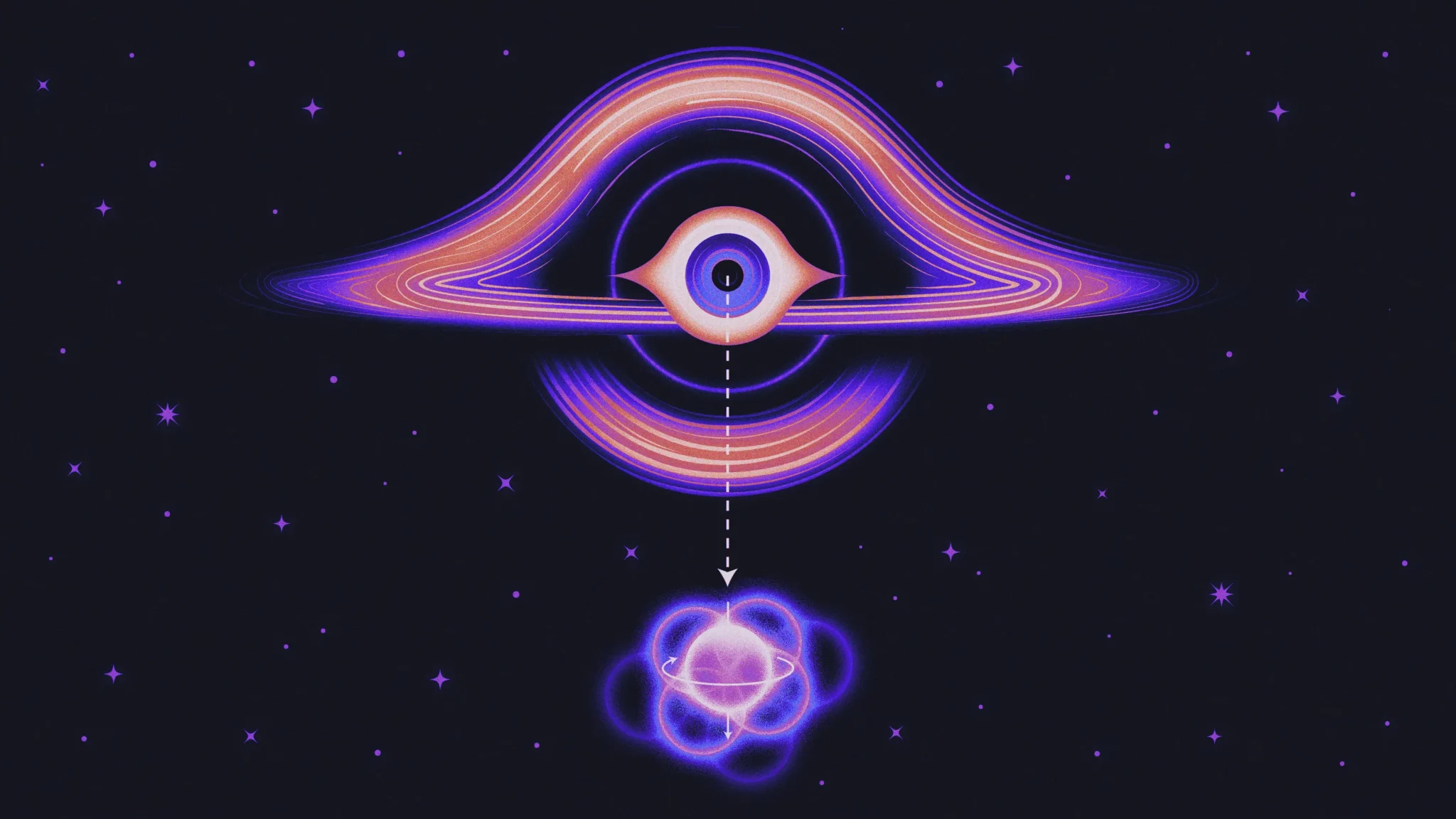

Well, that’s not it. Suppose there is an adversary who wants to destroy the coherence of the superposition. Despite your best efforts, decoherence can be achieved by measuring the superposed field. In this way, the superposition will be entangled with the measurement apparatus. Now, say the adversary is very snarky and decides to hide inside a black hole. The measurement is still possible since the field can penetrate the interior of the black hole. Are you sensing a problem? Well, if the laws of physics hold true, you cannot know whether a measurement has taken place, despite the entanglement. Thereby, to avoid any contradictions with causality and complementarity, we conclude that, irrespective of the actions inside, the black hole itself must decohere the superposition.

We expect that if a massive body is put in a quantum superposition of spatially separated states, the mere presence of a causal horizon in the vicinity of the body will eventually destroy the coherence of the superposition. This occurs because, in effect, the gravitational field of the body radiates soft gravitons into the horizon, allowing the black hole to acquire the differential information about the superposition.

Drafting is currently in progress. Sorry for any inconvenience. Please check back soon!